We know that the nesiim were held responsible for waiting too long to donate to the Mishkan. At first blush one might say that they did a great thing by not overwhelming the people with their gifts. By not giving anything until the end, if somebody had a dollar they felt that the dollar counted. In most campaigns today, if you’re on the low end of the campaign, its hard to believe that it makes any difference if you give or not. What was wrong with what the nesiim did?

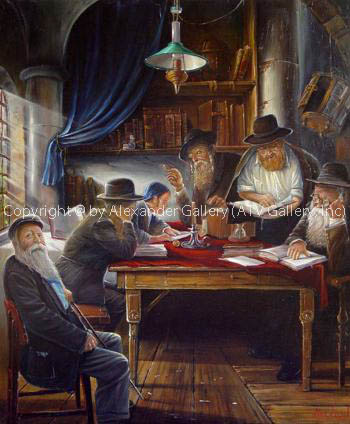

When the Vilna Gaon was once asked why he pushed himself to learn twenty hours a day, he responded, “If I learn twenty hours a day then the members of the Rabbinical Court of Vilna will learn sixteen hours a day. If they learn sixteen hours, then the Rabbis of the different congregations will learn twelve hours a day. If the Rabbis learn twelve hours a day, then the Rabbis in the villages will learn ten hours a day. If the village rabbis learn ten hours a day then the ballebattim will learn five hours a day. If I were to learn only fifteen hours a day, we would consider ourselves fortunate if the ballebattim would learn half an hour a day.”

Both philosophically and practically, there is a concept that the generation as a whole and every community respectively represents an organic configuration as if it were a whole person. Looking at Klal Yisroel as a whole, there is the tzadik hador, the Moshe Rabeinu of the generation, or the nassi as there were in many generations. The rest of Klal Yisroel represents different parts of that configuration. Some represent the ears of Klal Yisroel, those who are able to hear the heartbeat of the nation, where things are going, the necessity to respond to certain things. There are the eyes; there is the heart of the nation, the passion of Klal Yisroel. Some represent the support of Klal Yisroel, those who can contribute the money to sustain the whole structure. They are referred to as the legs or the thighs of Klal Yisroel. There are the people who are the people of action, and there are those whose primary contribution is in the realm of chessed, the arms of Klal Yisroel. This is all true both on a national level and as individual communities as well.

The relationship between the head and the body goes in both directions. The indiscreet thoughts of the head of Klal Yisroel or of a community ripple down through the “personhood” of its entirety. For example, when those thoughts reach the toes, the less exalted end of the spectrum, they have become more tangible than mere thoughts; they have become an impulse. If a leader is less than vigilant and indulged in even slightly ignoble thoughts, the impulse that he generates could result in action. The nation or community may, in fact, act out. Conversely, if a community is involved in actions which are not appropriate, when it ripples upward they become the kinds of things that torture the upper-end of the spectrum. Even though the leaders and heads are not given to action because of the deeds of the people, they will still find themselves anguishing over an inner struggle. This struggle may begin with the fact that they’ve allowed things to happen in their radius of influence, those very kinds of things that when they begin to evolve through the rest of the community, they finally end up tearing at the integrity of the leader. It’s a two-way street.

In a certain sense, what the Gaon of Vilna was saying is that his dedication to and his immersion in Torah has that kind of a ripple effect. Commensurate with the intensity of his commitment and discipline, will have a huge impact as to the commitment and discipline of the rest of Klal Yisroel. It commands a certain commitment on the parts of others, both in terms of quality and quantity. He found himself responsible for it, the locomotive. He had to put in all the thrust he could to get the caboose to start rolling.

Had the princes given upfront when it came time to contribute, their eagerness, their excitement, their purity of their unselfish disposition in giving, their yearning in giving would have been reflected in the way other people would have given both in quality and quantity. They were criticized for not giving upfront because it would have changed the way that everybody else would have given. By waiting until the end they end up like the tail wagging the dog.

(This piece was transcribed from a tape and edited for clarity of the written word only.)

Enjoyed this post? Get free updates by email or RSS.